Multimodal Storytelling with the Media Suite in the International Classroom

Berber Hagedoorn & Iris Baas University of Groningen, the Netherlands

In this blog post, we reflect on the use of the Media Suite for multimodal storytelling practices in the international classroom. The CLARIAH Media Suite combines Dutch media data collections and makes audiovisual material from Dutch audiovisual collections more accessible for higher education (CLARIAH Media Suite - What is the CLARIAH Media Suite?, n.d.). From October 2021 until January 2022, we explored the use of the Media Suite together with a multicultural, interdisciplinary group of MA students with a background in media creation and innovation at the University of Groningen. The students used content from audiovisual collections in the Media Suite for creative storytelling practices. In this subject tutorial, we provide insights on how the Media Suite can be implemented for multimodal storytelling usage in the international classroom.

There is a specific tension present when encountering audiovisual materials in an online archive such as the Media Suite: as very specific rich data, not only containing a mixture of sound and images. Here, an extra filter or layer of representation is added. For instance, the metadata entered by different documentalists (Hagedoorn et al., 2019). Together with the fast-developing field of digital humanities (and digital tools and methods) the demand for platforms and materials to teach digital humanities has increased significantly in the last decade (Rosenblum et al., 2016). Moreover, it has been suggested that digital humanities in the classroom can enhance the learning environment compared to traditional learning (Jokhio & Siddiqui, 2020). However, in the development of digital tools there has been little focus on geolinguistic diversity. In this context, “the digital humanities has much to gain, and much to offer, in engaging more fully with the languages-related cultural challenges of our era” (Spence & Brandao, 2021, p. 1). Because the Media Suite is an experimental, work-in-progress learning environment, there is a unique possibility to improve the tool based on real-use feedback from students in international, interdisciplinary learning environments.

The innovative aspect of the Media Suite lends itself to experiment with exploratory search tasks in (re)using the audiovisual archival collections containing all kinds of media and metadata. For this reason, the infrastructure is a useful tool for students to become familiar with iterative research processes, and with searching for information in new and different contexts. During the first semester of the MA Media Studies at the University of Groningen, various tutorials were designed to familiarize students with the concept of multimodal storytelling and exploratory search. Multimodal storytelling (see for example, Sylaiou and Dafiotis, 2020) includes the creative reuse and remix of diverse types of media content (television programmes, newspapers, oral history interviews…) and metadata to make new stories, ultimately providing a new creative storytelling product or experience “us[ing] multiple layers to present a story “(Wyman et al, 2011, p. 467) to individuals or groups. The goal for the students was to create a visual exhibition with materials found in the Media Suite. Students reflected on a case study and main research question around how specific media afford particular kinds of storytelling, or, how form plays an important role in the way we make sense of stories and therefore make sense of the world. In addition, they wrote an individual essay offering a meta reflection on the tool, the materials used and their research process.

Video lecture 1: Multimodal storytelling with the Media Suite in the international classroom

Teaching the Media Suite This subject tutorial is based on our experience teaching multimodal storytelling using the Media Suite to international, interdisciplinary classrooms of MA students at the Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. Through interactive tutorials in a co-creative lab setting, students carried out user tasks in class in order to get to know the tool in a playful and exploratory manner. The first tutorial focused on letting the students get familiar with the tool through tasks that were focused on the different affordances of the tool, comparing the Media Suite to other search tools such as Google. By doing this the students were able to recognise the importance of being aware of the impact of tool use in the research process.

During the second tutorial we focused on the iterative process of research using the three steps exploring, refining, and producing of stories (Sauer, 2017). Using hands-on user tasks, we challenged the students to think about possibilities, affordances and functionalities of the Media Suite tool as a mediating factor within the context of their research and the tool they are using. We explained this by introducing our own understanding of distant and close storytelling, based on the distant and close reading approach introduced by Moretti (2005) and explained by Jänicke et al. (2015). Close reading applies to interpretation of a text passage by the determination of central themes and the analysis of their development; and distant reading aims to generate an abstract view by shifting from observing textual content to visualizing global features of a single or of multiple text(s) (Jänicke et al. 2015.). The concepts of close and distant storytelling apply this idea to the way material is understood and then explained to an audience. Through conceptualizing this, the students gained a better understanding of why and how certain materials in the Media Suite can be (re)used and understood.

The third tutorial focused on the process in storytelling between author and audience; what different ways of storytelling are there and how does this impact the way an audience perceives the story? During this workshop the students were encouraged to think about how storytelling is part of their visual exhibition, and how their academic and personal experiences influence the story that is told in their visual exhibition, through reflective questions and discussion with their peers.

Video lecture 2: Creating a visual exhibition with the Media Suite in the international classroom

Multimodal storytelling with the Media Suite Multimodal storytelling can have different forms. In this section we will address the different ways our students used the Media Suite for multimodal storytelling: 1) storytelling through comparative analysis; 2) interactive storytelling; 3) storytelling from a historical perspective (multimodal timeline); 4) storytelling through case study analysis

*1. Comparative analysis of the Media Suite vs YouTube *For many students, working with archives like the Media Suite is a new form of doing research and digital search, as they are usually more familiar or comfortable with search engines such as Google. However, learning to work with archives like the Media Suite can be a beneficial step in growing one’s skill set for future research. In order to learn more about the affordances of the Media Suite compared to for example Google, comparative analysis displaying the differences between the two can be a good starting point.

Figure 1: Student example of comparative research using the Media Suite and YouTube

For example, students created visual exhibitions (in the form of video essays (Hinck 2013; Grant 2014) using materials from both the Media Suite and YouTube, in order to paint a picture of the differences when researching and creating a multimodal storytelling product. This not only illustrates differences in terms of experienced levels of serendipity (Sauer, 2017) while performing exploratory search tasks; it also shines light on the challenges of reusing copyrighted materials. Within the Media Suite, there is a clear distinction between materials that can be used within an educational context and outside university walls. The open collections are free to be used and reused, while other materials require a more delicate approach if shared or reused.

Initially students found that serendipity was more stimulated by other tools that were used simultaneously with the Media Suite, for example YouTube. Some students in turn found that while searching for specific content in the Media Suite was more challenging, however, the process made them more aware of the possibilities that arise when widening their horizon through exploratory search of an archive rather than using a traditional search engine for digital search. Moreover, they reflected that the Media Suite allowed them to tell a different kind of story compared to, in this case, YouTube. One student stated for example that they were “encountered with materials that were not originally in our primary research area but became inspirations of a new way of how our storytelling could evolve”. Even though using new tools can be a challenge, comparative research performing exploratory search can also be a good way to get to know different tools and learning how to use them, especially in terms of how tool use and digital search influences the research process. If you are interested in learning more about specific and data rich information, a comparative pilot study can therefore be a good way to get more familiar with the Media Suite.

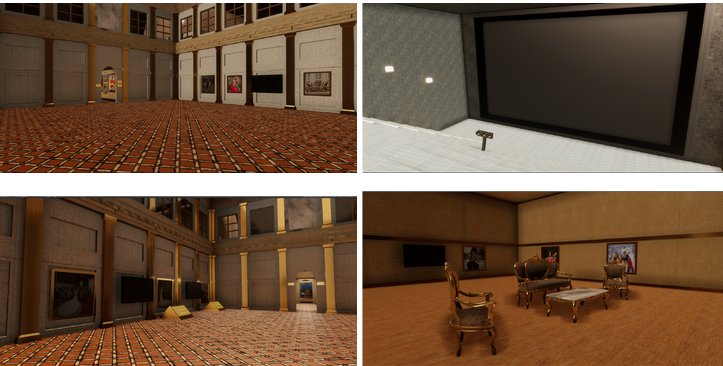

*2. Interactive storytelling *An important part of multimodal storytelling is finding creative ways to bring a story across to your audience, using the different narrative modalities of media types to the fullest (see e.g. Elleström 2019). While creating a video essay can be an effective way to do so, multimodal storytelling is not limited to this. Some students created for example an online museum exhibition, where users could “walk around” and interactively engage with materials in a digital museum environment, as depicted in the screenshots below. Inspired by the research publication “Storytelling in Virtual Museums: Engaging A Multitude of Voices” (Sylaiou and Dafiotis, 2020), one student states for example that they “[..]chose to go with this more interactive format so that people using it would be able to take the narrative in at their own pace, and create an individual experience, hopefully leaving a more lasting impression than a video essay format by giving them the ability to “play” with the narrative”. As this student points out, interactivity can be an effective way to make an audience engage with content, and may aid in powerful multimodal storytelling practices.

Thinking about effective storytelling ‘from author to audience’ requires creative thinking, and moves beyond visualization. It is therefore important, throughout the process, to consider what information needs to get across to whom, and what audience you are envisioning to engage with and understand the content (Sylaiou & Dafiotis 2020; Hagedoorn & Sauer 2018; Sauer 2017). Thinking about different creative ways to achieve this is therefore encouraged.

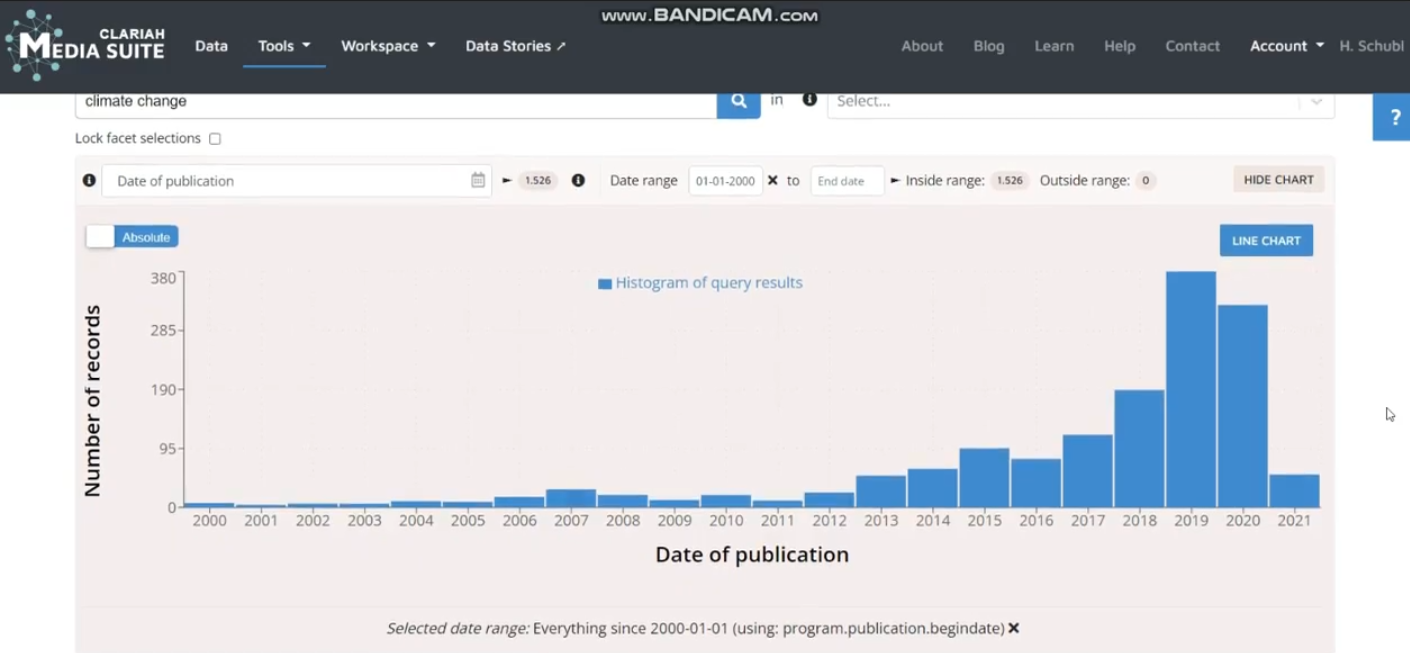

Figure 2: student example of interactive storytelling: a virtual museum experience centred around the Dutch Royal family

*3. Storytelling from a historical perspective: multimodal timeline *The affordances of the Media Suite allow users to create an overview of archived materials over time; such a timeline demonstrates when and what materials have been archived. The combination of collections available provides the opportunity to search in a quite complete archive of materials, allowing a historical overview of how certain topics are covered in different kinds of Dutch media. For example, the histogram function can be used to create a first overview of materials the Media Suite contains within a certain time frame on a certain topic, as shown in the screenshot below.

Figure 3: student example of using the timeline affordance in the Media Suite

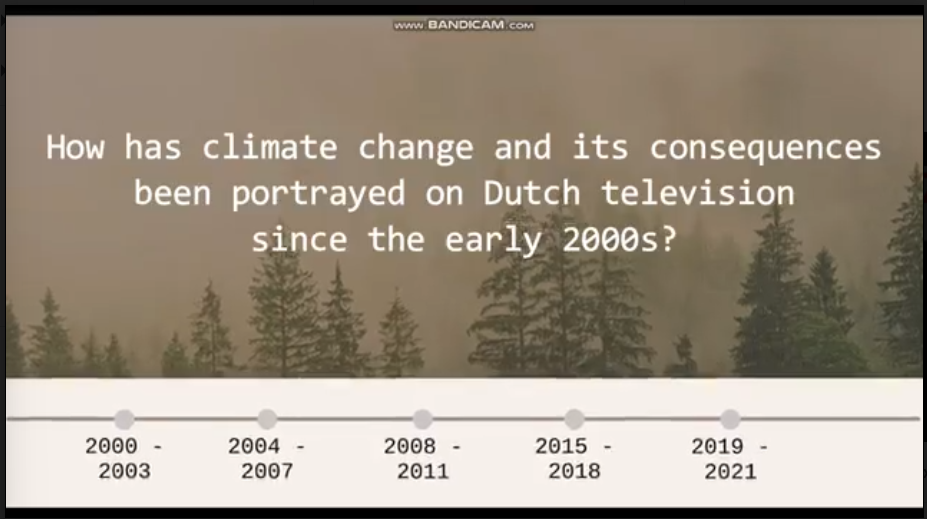

Multimodal forms of storytelling can be used to display these historical overviews creatively. Questions that can be asked, for example, are “how has the portrayal of a certain topic changed over time in a certain time period?”

Figure 4: Student example of a multimodal timeline (video essay)

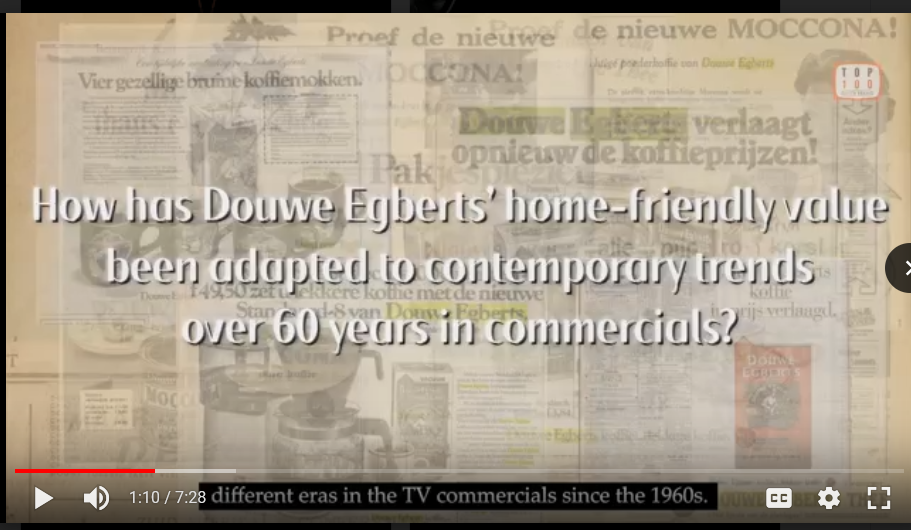

However, to answer these kinds of questions, basic knowledge of the Dutch language is preferable in order to analyse the found materials. One group for example, focused on the history of coffee culture in The Netherlands. However, due to language barriers they were unable to analyse materials in the Media Suite on a content level. Therefore, the group decided to focus on an aspect that they could understand; the visual aspects of commercials. As is demonstrated in the screenshot below, the students decided to focus on how non-verbal communication and visualization in the materials can be understood and analysed.

Figure 5: Student example of a multimodal timeline (video essay), focusing on non-verbal communication and visualization in found audiovisual archival materials

4. Storytelling through case study analysis The Media Suite also lends itself for in-depth case study research of a specific concept or phenomenon within Dutch culture as portrayed in and by its audiovisual archival collections. This is also relevant in an international classroom in the Netherlands, as searching for content in the Media Suite, in a way, allows for a serendipitous and playful understanding of parts of Dutch culture. A few students did so by focusing on the genre of Dutch reality TV, where one student stated that “One of the first things you think about when mentioning reality television is the show Big Brother. While the program format is known in many countries, it was interesting to learn that the original had been a Dutch concept [i.e. format]”. The student underwent this discovery by engaging specifically with Dutch archival materials. It demonstrates that using an environment such as the Media Suite can provide international students with a deeper understanding of the role of different media in Dutch culture.

Figure 6: Student example of case study analysis using audiovisual archival materials

Using different collections in the Media Suite, one can obtain a deeper understanding of certain concepts in Dutch culture and how they are portrayed in the media. However, especially for audiovisual content such as clips from television shows, the metadata does not provide extensive information for non-Dutch speakers. It can be advised to non-Dutch speaking users of the Media Suite to therefore use other tools such as Google, Google Translate or YouTube at the same time with the Media Suite to have more access to for example subtitles, or other materials that provide more context.

Challenges of a new tool For most students the Media Suite was a new tool, out of their comfort zone, as they were more familiar with search engine tools such as Google. Therefore, it was first and foremost important to teach the students the difference between the two, and why a tool like the Media Suite can be of additional value in their research and storytelling as a way of understanding the world. While doing so, the students did have some critical notes concerning the tool and its affordances; they found that there was a lack of explanation concerning certain affordances and facets in the tool, for example the variety of select options in the keyword selection field. Their impression was not necessarily that the tool should be simplified for students, however more information on how to use each of the options correctly would be preferable. Moreover, students were confused on how it’s not possible to select multiple collections at a time while searching for data. Especially for the projects where comparative research over multiple collections was performed, this was experienced as a disadvantage.

Challenges in the international classroom Using the CLARIAH Media Suite in an international classroom was challenging. While the tool itself seems to be developed for international users, many of the international students found it difficult to work with for multiple reasons. First of all, some of the facets have options in Dutch, without a translation. For example, the ‘genre’ option in the Sound and Vision archive – although the facet itself is English [Genre (series)], the selectable options are all in Dutch. This makes it difficult for international students to use and understand the tool, and prevents them from using it efficiently. As a solution for this, some students used web browser add-ons to translate the Media Suite website. This was not ideal and the additional necessary step makes the tool less attractive for international students to use. In addition to this, the materials found in the Media Suite are almost all in Dutch. While students have worked around this issue in creative ways, it was a challenge for them. At the same time, however, due to the language limitations, students were also more aware of the way the tool shapes research. During the tutorials the ‘work with what you have’ attitude was encouraged, which also is reflecting in their research process and final assignments. Interestingly, all groups took a different approach to the ‘work with what you have’ attitude; while one group used English search words in the hope to find English language content within the Media Suite, another group decided to translate keywords to Dutch to further specify their search. In their reflective essay, one student wrote that: “although the Media Suite did bring some hindrances such as being primary in the Dutch language, this has shifted the way one constructs their story. With regards to this, the three phases of exploring, refining and producing have contributed in shaping a coherent story and had to appropriately tinker our selected archives for a suitable visualisation”. Even though initially the use of a data-rich and specific archive can provide challenges, it also trains students to think critically about the content they are engaging with.

Most of the materials in the Media Suite are not only mostly in Dutch, in many cases the material is also culturally sensitive. One group of students focused on the culturally loaded figure of “Zwarte Piet” [“Black Pete”]. While at first the group found it difficult to fully understand the complexities of the debate, an interesting thing happened; by looking at the “Zwarte Piet” discussion from an outside perspective, one student started to reflect on similarities between Christmas traditions in their own country and the Dutch Sinterklaas traditions (the latter the “Zwarte Piet” figure is part of). This resulted in a critical thinking process, generated by the challenge of deconstructing a debate that was not familiar to this particular student. Therefore, the use of a predominantly Dutch tool in an international environment can also be of additional value in an international context. However, students and teachers need to be aware of this necessity to place the found materials into cultural context when teaching the Media Suite and using the tool in classes and assignments.

One way to aid students in this process is to let the students make groups with at least one native speaker Dutch. However, this is not ideal nor a sustainable way for using the tool in an international environment, as there might not always be a Dutch native speaker available. In addition to this, as one student pointed out “I was appointed to lead the search for material, as my team mates did not understand the Dutch language. Being raised with Dutch culture, my search behaviour was biased by this, as I based most of my search on prior knowledge that I had about the topic, namely the ‘Dutch Delta Works”. In this case, while knowledge of Dutch language and culture can be handy, it also might prevent other international students to engage with the Media Suite in a way where they grow their understanding of Dutch culture by serendipity and exploratory search where they engage with materials that provokes a diverse thought-process regarding the specific Dutch concept.

Reflection When using the Media Suite in an international classroom there are various aspects to consider. Without additional aid the tool, in its current form, does not lend itself for efficient and effective use in an international environment. Non-Dutch speakers have to use additional tools in order to translate the tool more completely or properly. This is a resolvable obstacle that would increase the usability of the tool significantly for non-Dutch speakers. Secondly, as most of the content found within the Media Suite is also in Dutch, this has prevented the students from using all affordances and possibilities the Media Suite offers to their full extent. For example, the ‘subtitles’ option for video material was extremely lacking in quality compared to the subtitles for Dutch content, making it almost impossible for non-Dutch speaking students to use this option. While students demonstrated creative ways to work with the materials, they felt the language barrier has prevented them from employing the tool to its full potential. We found that students were stimulated by the tool to rethink their research process and be more aware of the influence of tool use in their research. Thus, for the students the tool has contributed to critical thinking and search skills that are necessary for research in our contemporary media landscape, there is definitely room for improvement for the tool to be of additional use in the international classroom. Especially as thinking about strategies in working with archives is “working the other way around”, and in this manner, students are learning professional skills for storytelling, including digital search.

**Acknowledgements **With thanks to Susan Aasman, Sabrina Sauer, Lisenka Bakker & CLARIAH team.

References

-

Belmonte, M. I., Molina, S., & Porto, D. (2013). Multimodal digital storytelling: Integrating information, emotion and social cognition. Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 11. https://doi.org/10.1075/rcl.11.2.10alo

-

Bou-Franch, P. (2012). Multimodal Discourse Strategies of Factuality and Subjectivity in Educational Digital Storytelling. Digital Education Review. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ996783

-

Brailas, Alexios. Digital storytelling in the classroom: How to tell students to tell a story. International Journal of Teaching and Case Studies 8.1 (2017): 16-28.

-

CLARIAH Media Suite - What is the CLARIAH Media Suite? (n.d.). Accessed 12 January 2023, available at: https://mediasuite.clariah.nl/documentation/faq/what-is-it

-

Elleström L. (2019). Transmedial narration: narratives and stories in different media. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01294-6

-

Grant, C. (2014). The audiovisual essay: my favorite things. [in] Transition: Journal of Videographic Film and Moving Image Studies, 1(3). https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/audiovisualessay/reflections/intransition-1-3/catherine-grant/

-

Hagedoorn, B., & Sauer, S. (2018). The researcher as storyteller: using digital tools for search and storytelling with audio-visual materials. VIEW Journal of European Television History and Culture, 7(14), 150-170. https://www.viewjournal.eu/articles/abstract/200/

-

Hagedoorn, B., Iakovleva, K. and Tatsi, I. (2019). Data science contextualization for storytelling and creative reuse with Europeana 1914-1918. Europeana Research Grants Final Report. University of Groningen, 21 July 2019, abridged version.

-

Hinck, A. (2013). Framing the video essay as argument. The Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier, 1(2). https://teachingmedia.org/framing-the-video-essay-as-argument/

-

Jänicke, S., Franzini, G., Cheema, M. F., & Scheuermann, G. (2015, May). On Close and Distant Reading in Digital Humanities: A Survey and Future Challenges. In EuroVis (STARs) (pp. 83-103).

-

Jokhio, R. A., & Siddiqui, A. (2020). Investigating the Impacts of Digital Humanities on the Academic Performance of Second Language Teachers and Learners in Institute of English Language and Literature, University of Sindh, Jamshoro. International Research Journal of Arts and Humanities, 48(48), 237.

-

Moretti, F. (2000). Conjectures on world literature. New Left Review 1, 54.

-

Rosenblum, B., Devlin, F., Albin, T., & Garrison, W. (2016). Collaboration and coteaching: Librarians teaching digital humanities in the classroom. In A. Hartsell-Gundy, L. Braunstein, & L. Golomb (Eds.), Digital humanities in the library: Challenges and opportunities for subject specialists (pp. 151–175). Association of College and Research Libraries.

-

Sauer, S. (2017). Audiovisual Narrative Creation and Creative Retrieval: How Searching for a Story Shapes the Story. Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts, 9(2), 37-46. https://journals.ucp.pt/index.php/jsta/article/view/7287

-

Spence, P. J. & Brandao, R., (2021) Towards Language Sensitivity and Diversity in the Digital Humanities. Digital Studies / Le champ numérique 11(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.8098

-

Sylaiou, S. & Dafiotis P. (2020). Storytelling in Virtual Museums: Engaging A Multitude of Voices. In: F. Liarokapis et al (Eds.) Visual Computing for Cultural Heritage. Springer, pp. 369-388. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37191-3

-

Wyman, B., Smith, S., Meyers, D., & Godfrey, M. (2011). Digital storytelling in museums: observations and best practices. Curator: The Museum Journal, 54(4), 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2011.00110.x