Using the Media Suite in a Decolonial Classroom

Asli Özgen, University of Amsterdam

The CLARIAH Teaching Fellowship granted project, entitled Decolonising in the Media Suite: A cross-media analysis of race-related topics in Dutch media , focused on the benefits of using the Media Suite in a decolonial classroom with the purpose of supporting decolonial pedagogy. The project was carried out in the first edition of the new elective Decolonising Media Studies (DeMS). One of the four diversity-grant-winning electives at the University of Amsterdam, DeMS took place in the Spring Semester of 2021/2022 Academic Year. In the scope of this project, a decolonial classroom is defined as a safe learning environment where students, assistants, and teachers engage in a collective learning experience in a non-hierarchical, non-individualistic, non-competitive setting that supports collective work, mutual respect, intellectual enrichment and empowerment, and a critical awareness of global imbalance in the production of knowledge (i.e. latent structures of power benefiting white, heterosexual, male, abled body as the unfailing subject of knowledge production). In this setting, the Media Suite stood out as a helpful tool to conduct critical discourse analysis of race-related topics in the media as well as media archives. In the scope of the DeMS elective, the Media Suite assignment was thus an important part of the course. In this blog post, I first give some context about the initial observations and ideas that sparked this project. Later on, I discuss student experiences with the Media Suite assignment, and I conclude with a reflection on the outcomes. In this specific implementation of the project, the Media Suite proved to be a valuable tool to activate students in a decolonial classroom setting to design and conduct their own research-driven assignment, focusing on media analysis. On many levels, the project evidenced a richer potential that can be explored in future implementations and variations of the assignment that I’m focusing here. Students, teachers, and researchers can refer to the relevant tutorial to use this exercise in their teaching as well as research and adapt it where necessary to specific learning goals, student profiles, and classroom compositions.

First, why decolonise? The starting point for this project was to experiment with the Media Suite in a decolonial classroom. With colleagues Leonie Schmidt and Jeroen de Kloet, we submitted a proposal for an elective that would inform students of the ongoing debates on decolonising the education, as well as encouraging them to put some of these theories into practice in their immediate classroom environment. For example, establishing connections beyond the university with communities, community centres, memory and archive institutions, and cultural venues was a major idea. Encouraging students to explore their cultural repositories and bring their knowledges to the classroom in a safe environment was another component of the elective that we cared about.

Media Studies is a rapidly growing area of study that appeals to an increasingly diverse student profile. Decolonising Media Studies: From Theory to Practice addressed two closely linked problems in this context. Firstly, some students feel alienated in an almost exclusively western-dominated curriculum about media history, theory, and practice. Secondly, they remain unaware of the relevance of their (intersectional) cultural background to their chosen field of study. DeMS aimed to bridge this disconnect and encourage students to build upon their own cultural repertoires and knowledge. Addressing the first problem, DeMS adopted a student-activating pedagogy, where students determined readings, media examples, and assessments. To tackle the second, the students were given the opportunity to collaborate with a number of cultural institutions and local partners (such as Black Archives, Institute for Sound and Vision, Cavia, etc.) to reflect on their societal positions. On both of these levels, the CLARIAH Media Suite offered a significant potential, which was the starting point for this project.

Since the course did not rely on lectures, group discussions played a pivotal role to facilitate students’ learning journey and research, eventually leading to their final assignment. Students were given three options to choose as their final assignment. These options did have some guidelines but they also provided ample freedom to students to follow their own interests. Lecturers and assistants worked closely with student groups to facilitate their learning and research explorations. One option promoted establishing connections with communities beyond the university, and the second option focused on zooming in on the absences, gaps, and assumptions in the media curricula. The third option was cross-media discourse analysis, using the Media Suite.

The project envisioned using Search, Bookmarking and Annotation functionalities to activate students to design their own small-scale research projects. One of the project aims was to develop an understanding of how cultural heritage repositories are preserved and made accessible, based on the collections included in the Media Suite. As such, students would be able to bridge the media analytical skills they obtain in the curriculum with their own cultural knowledge. Building on this, they would approach questions of race in relation to audio-visual collections stored in major cultural institutions (such as Institute for Sound and Vision, Eye Filmmuseum, DANS, etc.) from an analytical perspective.

Experiences with the Media Suite In the first session of the elective, students formed small research groups (of 3-4 students) and chose a topic. Suggested topics included, but were not limited to, the coverage of (a) #BlackLivesMatter protests; (b) immigration and refugee ‘crisis’, specifically in the context of kinderpardon and/or the recent general elections; (c) het racismedebat hosted by NPO1 but sparked discussions and alternative events across various platforms; (d) colonial past, linked to the city heritage, colonial artefacts at museums, and a possible ‘pardon’ for Dutch involvement in the slavery trade. Students could also propose another relevant topic of their choice.

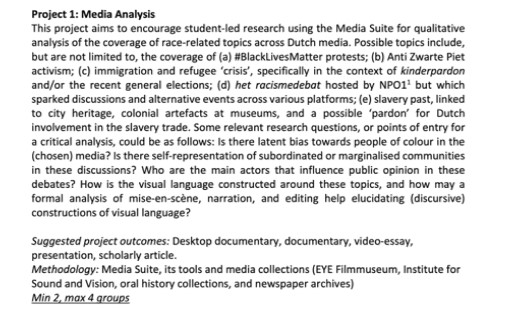

In the implementation of the project, the Media Suite assignment was one of the three options that students could choose from (see Image 1 below) to give the 6 student groups some flexibility to form their own assignments, in line with the decolonising pedagogy. Two groups chose this assignment.

Image 1: Assignment description from Decolonising Media Studies Course Manual (2021-2022)

The two groups conducted research on “Anti-Asian Racism in the Netherlands” (Group 1) and “Rap and Intersectionality” (Group 2). Both groups made use of the Media Suite in their research phase. However, there were also some challenges that provided interesting insights, which I elaborate below.

Students carried out their research projects in two phases. In a first ‘exploratory’ phase, they familiarised themselves with the Media Suite’s functionalities and began building a corpus. At this stage, groups received hands-on tutorials about the Media Suite. In the project description, it was proposed that an expert would give this tutorial. However, given the small size of two student groups (a total of seven students), I introduced them to the Media Suite and taught how to use the key functionalities. Students were also referred to the available sources on the Media Suite Learn page. They watched tutorial videos and read tutorial descriptions. They acquired the skills to use the available tools such as Search, ASR Data Search Layer, Bookmarking, and Video Annotation. Using these skills and tools, groups researched the collections available and searchable in the Media Suite; primarily television, radio, and newspaper archives.

In a second ‘analytical’ phase, students analysed their chosen corpus in consultation with their supervisor. Based on their findings, the groups discussed suitable products to share their research results. The options proposed in the project description were (a) a discussion paper, containing a close analysis of research findings supported by a theoretical framework, and a visual presentation of the media items (based on their annotations) (b) a blog post, which can be considered for publication at the CLARIAH portal; (c) an in-class presentation of their findings, supported by a theoretical framework and visuals; (d) a short desktop documentary (based on the relevant Media Suite tutorial). Group 1 chose to make a website that provides in-depth information about and examples of Anti-Asian Racism in the Netherlands as well as grassroots activism against such manifestations of racism. The cross-media aspect of this assignment was very strong. The group members did extensive research on social media such as Instagram as well as collecting cases from television, radio, and newspapers. In their website, which they conceived literally and metaphorically as a platform to chart out the different forms and manifestations of Anti-Asian Racism as well as antiracist struggle against these aggressions, the group brought these cross-media examples together as well as their analytical readings, using quotes from Stuart Hall and Edward Said among others.

Group 2 decided to share their findings of Rap and Intersectionality in the form of a multi-sensorial exhibition, which they set up at the BuzzHouse, UvA Media Studies’ flexible working space for students. Since this group was composed of students from entirely different backgrounds speaking entirely different languages, the group turned this diversity into a topic of study. The starting point was discussing their own positionalities and reflecting on their own intersectional experiences. Based on these reflections, the group decided to study the discourses of intersectionality as represented in the rap genre. Each member would bring a rap musician from their own cultural background (could be their country of origin or mother tongue). This project also had a strong cross-media component. Each member conducted their own analysis of a media component of their choice, e.g. lyrics, visuals, costume, bodily performance, or semiotics, etc. Depending on this, each member also had the task to determine the best way to present their analysis and findings. While one student decided to print some stills from the music video on polaroid paper to emphasise the ephemerality and vulnerability of the ‘immigrant’ – a theme in the chosen rap song –, another student took inspiration from the musician’s personal story in the song to place a ‘diary’ on the table so that visitors can write down (as well as contemplate on) their own intersectional experiences. In this group, as well as in the Group 1, there were only one Dutch-speaking student, who mainly had the task to excavate the collections searchable at the Media Suite. The Dutch-speaking student came from a Hindustani background, and they wanted to emphasise the ableist standards of the music industry by focusing on a deaf rap musician from the Netherlands (namely, Sor). The student excavated the collections searchable in the Media Suite to find the coverage about Sor, specifically regarding the discussions about his hearing disability.

Challenges of working with Media Suite in an international setting The first challenge encountered in the implementation of this project was interdisciplinarity and this was primarily an outcome of the university’s elective policy. At the University of Amsterdam, the electives are offered faculty wide. This gives students freedom to choose any elective regardless of their host programme. While this allows students to follow an elective in a topic that they are interested in, as well as making the classroom a diverse and interdisciplinary environment, in the specific case of DeMS it presented several difficulties. Most importantly, some students were not readily familiar with media analysis methods. This made it sometimes difficult to adhere to the research directions proposed in the assignment description, such as: Is there latent bias towards people of colour in the (chosen) media? Is there self-representation of subordinated or marginalised communities in these discussions? Who are the main actors that influence public opinion in these debates? How is the visual language constructed around these topics, and how may a formal analysis of mise-en-scène, narration, and editing help elucidating (discursive) constructions of visual language? Only a limited number of media students could engage with such questions.

Still, the classroom was eventually quite a welcome mix of disciplines, with students coming from as diverse programmes as political science, religion, sociology, communication science, among others. These students brought interesting insights into the discussion of decolonisation as a topic. But they had difficulty to navigate the Media Suite. In my feedback sessions, I realised that quite a few students were not familiar with archives. They had no experience with archival research. On this point, one question that came up in these sessions was quite emblematic: A student asked how Media Suite is different than YouTube, and if they cannot “just find the same video on YouTube.” Following this, it was productive to have a discussion on the ways in which YouTube functions / doesn’t function as an archive. Plus, we talked about other functionalities that the Media Suite incorporates to facilitate digital-humanities-informed scholarly research, as well as the research questions that these functionalities enable. These two instances show that students were intimidated to start exploring the Media Suite. I believe this reveals more an anxiety about how to start searching/navigating the collections rather than a user-friendly interface.

The second challenge was language diversity. The DeMS classroom was exceptionally international, with students coming from a wide range of nationalities (such as Greek, Polish, Ukrainian, Hungarian, Kazak, Lebanese, South African) and mixed cultural backgrounds (such as Hindustani-Dutch, Mexican-Spanish, Greek-Flemish, Turkish-American, Chinese-American among others). In this fascinating diversity, only 2 students (out of 27) spoke Dutch.

In CLARIAH Media Suite Teaching / Research Fellowship gatherings, a few colleagues who had experience with using the Media Suite in international classrooms touched upon the challenges for non-Dutch-speaking students before. One solution proposed by the colleagues was to include at least one Dutch speaker in assignment groups. However, the solutions suggested and discussed in those gatherings were not applicable in the specific case of DeMS. Initially, most students felt intimidated by the language barrier and moved away from the Media Suite project. In the end, there were two groups (out of 6) working on Media Suite projects, and there was one Dutch speaking student in both groups. However, this affected the group dynamic sometimes in negative ways, as other students felt excluded or disconnected from the work. Surely this is not strictly and only the outcome of Media Suite, it’s a challenge that needs to be addressed at a wider context of collective working culture of students. In a standard pedagogical system, students learn to perform individually in a competitive environment. It takes a longer time to shed these habits aside and learn to collaborate collectively, equally, and respectfully on a shared outcome. Such a cultural shift doesn’t happen overnight, and many students bring such habitual values into a decolonial classroom setting too.

To overcome the difficulties non-Dutch-speaking students faced when working with Media Suite, I advised them to expand their research to other media (for example, silent films or image-based collections) to strengthen/contribute to the cross-media aspect of the assignment. However, this solution also had its own limitations. It resulted in the fact that Media Suite (findings) were not anymore the centre focus or the main component of the assignment; they were supportive findings. To address the challenges of language diversity, I have a few suggestions. First, a tutorial on working with image-based collections (such as Desmet Poster Collection) for users that do not speak Dutch could be an enriching option to take the best out of Media Suite collections. Second, ensuring better visibility of other languages in the Media Suite collections. For example, in my own research, I did come across Turkish-language items in Sound and Vision collections. Perhaps Curated Playlist(s) shedding light on other languages could be one way to show the language diversity of the collections accessible via the Media Suite. Similarly, a tutorial on working with / accessing other languages in the collections could address this issue. Finally, better explaining which queries, functionalities, tools can be used to excavate and access non-Dutch items. For example, are these languages marked in Dutch (e.g. Turkish-language television programmes are marked as ‘Turkse Uitzending’), or are there any words in the metadata in that language (again, staying with the same example, is it possible to type in query words in Turkish? Can you or should you use Turkish letters? Are there any non-Dutch words in the metadata)? Can the ASR tool recognise languages other than Dutch?

Conclusion I believe the project yielded meaningful insights to enrich learning experience, and it’s thanks to the contributions, incisive questions, and unyielding enthusiasm of the students of the DeMS elective that these meaningful insights came to the fore. One of the main aims of this project was to build on efforts to engage with postcolonial perspectives in the Media Suite Learn initiative and to offer concrete examples of teaching race-related topics. On this point, the tutorial that is based on this project is a promising beginning point for teachers looking to experiment with research-based learning of race-related topics using the Media Suite. The tutorial presents further possibilities for variation and when it’s shared on Media Suite Learn, it might inspire similar projects.

Second, it was envisioned that the project might provide valuable experience for student-activating teaching using the Media Suite. On this point, the project also brought meaningful outcomes and feedback. In line with the aim to decolonise, students had full autonomy to design research within the possibilities of Media Suite and to bring their own diverse interests in contact with the media analysis skills that they obtained in the programme. The project thus affirmed the rich diversity and decolonial methodologies the Media Suite might support.

Third, on a technical level, the project aimed to develop collective working models on Media Suite interface. As I described earlier, some working models in the group assignment (e.g. Group 2) provided some ideal models to overcome the absence of a shared project space. In the proposal, it was argued that, thanks to its interdisciplinary character, the project may also produce relevant findings for other Work Packages, specifically Text and Linguistics. While this was not an active component of the projects conducted within this edition of DeMS elective, it certainly is relevant and might be more actively encouraged in the future implementations of the tutorial based on this project.