Tutorial: Identifying ‘flow’ in linear television programming with digitised newspapers and the Media Suite

Mary-Joy van der Deure and Jasmijn Van Gorp, Utrecht University

Tutorial description, case and objectives

In 1975, Raymond Williams published his acclaimed work

Television: Technology and Cultural form

. In this book, he describes how television as a medium is characterised by

flow

. Instead of separate, individually consumed objects, television broadcasts became a sequence of items that could no longer truly be distinguished as distinct bodies of work. Williams describes this flow both in terms of

technology

, meaning the materiality behind television, as well as its role as a

cultural form

where it shapes and is shaped by daily life. While the medium of television has been transformed to a great extent since the linear viewing William’s spoke about in the 1970’s, his conceptualisation of flow remains useful to understand the medium’s transformation into modern-day forms of viewing, such as streaming video on demand (SVOD) services.

It is important to understand television’s history, both because of its reflection and alteration of society, but also to understand the contemporary embodiments of the medium. This tutorial contributes to this understanding by providing a

theoretical reflection

on television history and Williams’ conceptualisation of flow. Simultaneously, it will apply this to the historic Dutch broadcasting system and offer a practical

exercise

to implement this conceptualisation.

In this tutorial you will:

-

Learn about, and reflect upon, the concept of flow as described by Williams (1975)

-

Gain a better understanding of linear television

-

Get familiar with Dutch broadcasting history

-

Get accustomed with the Weekly Recordings collection in the Television archive of the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision

-

Learn how to conduct a “long-range” flow-analysis

Types of teaching and research

This tutorial is aimed at BA or MA students who are becoming familiar with television theory and television historical research. For this tutorial it is a prerequisite that you know how to login to the CLARIAH Media Suite. If you are unfamiliar with the Media Suite, it is recommended to first follow this tutorial on logging in and setting up a user project. It is recommended for students to individually work through this tutorial, which takes approximately 90 minutes to complete. Results of the tutorial assignment and reflection questions can thereafter be discussed in-class, which takes an additional 30 minutes.

Mandatory reading:

- Read chapter 4, up to and including ‘long-range analysis’ (pp.77-100) of Williams, Raymond. Television: Technology and Cultural Form. London & New York: Routledge, 2003.

Recommended reading:

-

Cox, Christopher. 2018. ‘Programming - Flow in the convergence of digital media platforms and television’. Critical Studies in Television 13 (4): 438-454.- Hagedoorn, Berber. ‘Dutch television studies and the reinvention of television as a medium in practice.’ Critical Studies in Television 16, no. 2 (2021): 196-209.

-

Wijfjes, Huub. ‘Inleiding: Zeventig jaar televisie in Nederland’. In De Televisie: Een Cultuurgeschiedenis. Amsterdam: Boom, 2021.

Tutorial structure

This tutorial will first provide a

theoretical introduction

to Williams’ conceptualisation of flow in linear broadcasting. Hereafter, the situation in the Netherlands will be addressed through a quick summary of the

Dutch historic broadcasting landscape

. Finally, this theory will be applied in the

tutorial assignment

, where students will compare a historic Dutch television schedule with an archived recording to understand how flow can be identified.

Please note:

As this tutorial works with a very large ‘Weekly Recording’ video file, it is possible that you will come across some loading problems in the Media Suite. We are working to resolve this issue. If you encounter this problem, it is recommended to refresh the page. If this does not work, please log out and log back in again. Please also work in Google Chrome, as this works best with the Media Suite.

Acknowledgements

This tutorial was made as part of the AI-Tada project on Automated indexing of historical television data, the Click-NL RE-FRAME project and CLARIAH WP5: Media Studies (NWO). It is also part of a full-length journal article we are currently working on (once published, you will find this article here ). We would like to thank Judith Keilbach for feedback on the earlier version of this tutorial.

Television history

Linear television and the concept of ‘flow’

Let’s first take a closer look at Williams’ conceptualisation of ‘flow’ . In the beginning of his book, Williams addresses the statement that television has altered our world. In this contemplation, he diverts from the notion that technology is the driving force behind social change and progress. In this line of thought, called ‘technological determinism’, our ‘modern world’ has been created by different technological inventions, such as the steam engine, the atomic bomb, but also media such as television (Williams 1975, 5). Instead, Williams argues that, while technology plays a role in societal development, its impact and position are determined by social and cultural factors . Technology is intertwined with society and culture. In his approach towards television, Williams sees the medium both as a technology and as a cultural form . This means he goes beyond television as a simple means of transmission, but that he considers the way this technology is embedded in society and how it reflects societal norms and culture. It is also in this context, in which he analyses television as ‘flow’.

In the early days after its invention, television programmes were frequently interrupted. During the night and large parts of the day, there were no programmes to broadcast. This slowly evolved into a flow through the search for new forms of revenue. Programming expanded into all parts of the day and commercial, and later public, television channels started airing advertisements in-between programmes.The individual programmes were strung together by different sequences, together forming one viewing experience .

‘What is being offered is not, in older terms, a programme of distinct units with particular insertions, but a planned flow, in which the true series is not the published sequence of programme items but this sequence transformed by the inclusion of another kind of sequence, so that these sequences together compose the real flow, the real broadcasting’. (Williams 1975, 91)

Later on, this was supplemented by another sequence, the trailers and announcements of the programmes that would follow that same day. The intention, and result, of this type of programming is a continuous flow designed to keep the viewer engaged and watching as long as possible. Williams describes this as a flow because the different items are interwoven into one unified experience , that of ‘watching television’. This is particularly the case for commercial television, where programmes, advertisements, and promos are intertwined in a sequence as flow, making it difficult to distinguish between separate units.

Williams illustrates this theory with a flow analysis on three levels. Firstly, a long-range analysis, where he analyses the order of programmes broadcast on one day. Secondly, medium-range, where he analyses the flow of items within a single news broadcast and thirdly, close-range, where he focuses on the exact words of the news broadcast. In this tutorial we will focus on the first type: a long-range analysis of a broadcast schedule.

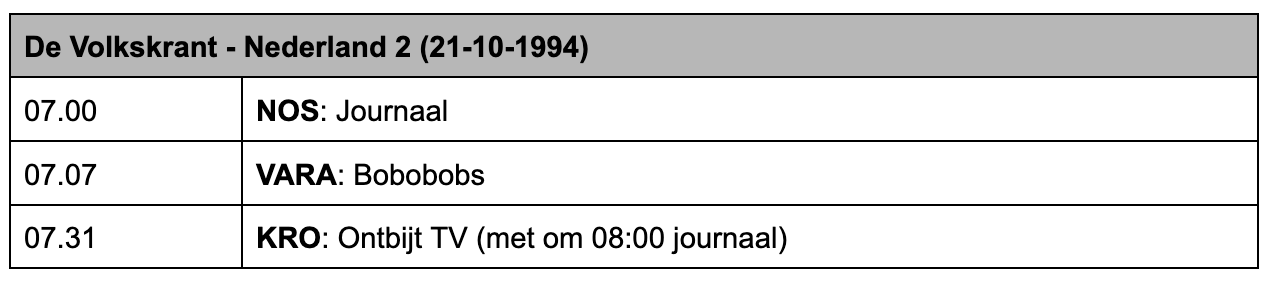

See, for example, the two images below. Figure 1 is a scheduled morning of television in 1994, as published in Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant . We accessed this television schedule through Delpher , the newspaper database of the Royal Library (KB). Here, you can access historic Dutch newspapers up until 1995. After this date, it is advisable to search in the commercial database NexisUni at your university library (e.g. here the one of Utrecht University). In figure 1, the schedule shows only two actual programmes between 07:00 and 10:40, after which the broadcast ends and proceeds later in the afternoon.

Figure 2 , however, shows what was actually broadcast on that morning. In between the programmes, announcements are present which were adjusted to the children’s programme that will be aired soon after. There are also animations, reminding the viewer of the channel they are watching, and even a clock, counting the minutes until the programme starts. This continuous transmission is a key characteristic of television as a technology. Flow is present in television as both a technology and cultural form.

Figure 1:

A morning of scheduled television on Nederland 1 in 1994, as published in De Volkskrant on 21-10-1994. Accessed through

Delpher

.

Figure 2:

A morning of television on channel

Nederland 1

21-10-1994, as was actually broadcasted and archived in the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision. The published schedule in figure 1 was compared to the Weekly Recording in the archive. This specific weekly recording was accessed through the Media Suite, and can be found

here

, as segment 3.

Dutch broadcasting history

Now we have a clear understanding of Williams’ conceptualisation of ‘flow’, as well as an example of what this looks like in practice, it is also important to understand the specific historic situation in the Netherlands . In his description of flow, Williams talks about analogue, linear television. In the Netherlands, the first television broadcast was on October 2, 1951 and by 1970 most households had a television set in their home (Wijfjes 2021; Canon van Nederland n.d.). A characteristic of the Dutch broadcasting system was that it was structured according to the ‘pillarised’ society. This entailed that Dutch society was divided in different pillars, depending on ideological, religious or socio-economic backgrounds (Hagedoorn 2021, 197). This pillarisation influenced media consumption, where households often read the same newspaper or listened to the same radio broadcasters. This system continued into the television age. The four largest broadcasting associations, NCRV, KRO, AVRO and VARA, were all placed under the NTS (the Dutch Broadcasting System). They each divided the airtime and produced their own programmes, and to this day, these broadcasters are present on the channels of the public service broadcaster NPO.

In 1992,

commercial broadcasting channels

were introduced in the Netherlands (Hagedoorn 2021, 197), which increased competition and the need to retain viewers’ attention. It was not until the year 2000, that the Dutch television system started digitising and today, NPO programmes can also be viewed on-demand through

digital platforms

(Huub Wijfjes 2021). Understanding the history of the medium, however, is still important, as linear broadcasting and its organisational structure have shaped television as we know it today.

In what follows, you will analyse a morning of linear television broadcasted in the Netherlands in 1994, similar to the example in figure 1 and 2. Through this exercise, you will learn to apply Williams’ conceptualisation of flow, while also engaging with Dutch television history.

The tutorial assignment

In this assignment, you will annotate a television schedule according to the long-range analysis as described by Williams. The published television schedule describes the programmes that will be aired that morning. However, according to Williams, this does not represent the actual television viewing experience of that day. Through the preserved broadcast in the archive, it becomes possible to supplement this schedule with more details of what was broadcasted. Similar to the example previously shown in figure 1 and 2, you will annotate the schedule to include all interstitials such as commercials and announcements. By understanding which programmes were actually aired, and what was shown in between, we gain insight into the televisional flow.

A collection that is very apt to study the concept of flow are the ‘ weekly recordings ’ [integrale opnames]. Each year the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision archives two full weeks of Dutch television. While the archive normally preserves individual programmes, these weekly recordings additionally contain everything in-between the programmes, such as commercials and announcements. These recordings are a fruitful source for television historians, as they incorporate the context in which the programmes were initially broadcast, namely the televisual flow. We can thus use these recordings and compare them with the published schedule, to map the broadcasted flow.

Tutorial steps

Figure 3: A morning of scheduled television on Nederland 2 in 1994, as published in De Volkskrant on 21-10-1994. Accessed through Delpher .

Step 1: Locating our case study in Delpher and the Media Suite

-

Before you start annotating, first get familiar with the television schedule above, in figure 3. This schedule represents a planned morning of television, as was published in De Volkskrant on October 21, 1994. (If you want to do this exercise with a different schedule you can find digital newspapers up until 1995 through https://www.delpher.nl/ .) This is the same October day as the example in figure 1 and 2, but a different channel.

- Go to the Delpher website , and look at the original television schedule. Study this schedule and write down what you find special about the schedule in terms of form and content. How many channels do you see?

-

Now, we are going to retrieve the video of this television morning on ‘Nederland 2’, through the preserved ‘Weekly recording’ in the Media Suite.

-

To access this recording, go to the Media Suite and log in.

-

Go to the ‘Nederland 2’ Weekly Recording of 21-10-1994, which can be found here . In this recording, navigate to segment 4 in the drop-down menu above the video.

-

Please note: If you have any trouble loading the video, please refresh the page.

-

Figure 4

: The weekly recording video in the Media Suite you will be using, which can be found

here

. You will specifically access Program segment 4.

Step 2: Annotating the schedule

-

Now you found the right video, you are all set to start annotating.

-

Copy-paste the schedule in figure 3 in a new Word document to create a version of the broadcast schedule which you can edit.

-

Compare the pasted broadcast schedule with the preserved morning of television in the archive and annotate the schedule in your Word document.

-

Colour the table cell green through the shading option when the programme was broadcast

-

Colour the table cell red if the programme was not broadcast and thus not part of the video

-

Add all items that are not present in the broadcast schedule but are present in the video, and colour these table cells blue . This includes all individual commercials, announcers, previews etc. Try to describe the details you see, for example, what logos are shown and what music do you hear?

-

Pay specific attention to the programme ‘KRO: Ontbijt TV’ and note how this intertwines with the rest of that morning’s television.

-

See figure 4 for an example of what your schedule will look like.

-

-

Well done! You now have an overview that represents the televisual flow broadcast on the morning of 21-10-1994. Read through your annotated schedule, and continue to the reflection questions in step 3.

-

Please note : You don’t have to add the time the items aired, as the exact broadcast time will be hard to determine.

-

If you want to navigate through the recording, it is recommended to do so with the timeline below the video, as this is more accurate then the navigation bar in the video itself.

-

Figure 4 : An example of an annotated schedule for channel Nederland 1 . You will annotate the schedule for channel Nederland 2 .

Step 3: Reflection questions

Now you have a more factual representation of the flow broadcast on this date, take some time to reflect upon what you see. Answer the following questions:

1. What type of items were not present in the broadcast schedule?

2. Where can you identify the different broadcasting organisations, remnants of the previous pillarisation in Dutch society?

3. Where can you identify flow in the commercials broadcasted in-between the programming?

4. Where can you identify flow in the other interstitials in this broadcast (announcements, leaders etc.)?

5. Where can you identify flow in the programming itself?